By Dieter Roelstraete

He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging.

—Walter Benjamin1

[Preliminary admonition: there is no disgrace in seeking to define either the essence or the attributes of art. For…]

…art is, or at least can be, many things at many different points in time and space. Throughout its history—which is either long or short, depending on the definition agreed upon—it has assumed many different roles and been called upon to defend an equal number of different causes. Or, alternately—and this has turned out to be a much more appealing and rewarding tactic for most of the past century—it has been called upon to attack, question, and criticize any number of states of affairs. In the messianic sense of a “calling” or κλησις—a call to either change or preserve, for those are the only real options open to the messianic—we might locate both the roots of art’s historical contribution to the hallowed tradition of critique and the practice of critical thought, as well as its share in the business of shaping the future—preferably (and presumably) a different future from the one that we knowingly envision from the vantage point of ”today.”

In the present moment, however, it appears that a number of artists seek to define art first and foremost in the thickness of its relationship to history. More and more frequently, art finds itself looking back, both at its own past (a very popular approach right now, as well as big business), and at “the” past in general. A steadily growing number of contemporary art practices engage not only in storytelling, but more specifically in history-telling. The retrospective, historiographic mode—a methodological complex that includes the historical account, the archive, the document, the act of excavating and unearthing, the memorial, the art of reconstruction and reenactment, the testimony—has become both the mandate (“content”) and the tone (“form”) favored by a growing number of artists (as well as critics and curators) of varying ages and backgrounds.2 They either make artworks that want to remember, or at least to turn back the tide of forgetfulness, or they make art about remembering and forgetting: we can call this the “meta-historical mode,” an important aspect of much artwork that assumes a curatorial character. With the quasi-romantic idea of history’s presumed remoteness (or its darkness) invariably quite crucial to the investigative undertaking at hand, these artists delve into archives and historical collections of all stripes (this is where the magical formula of “artistic research” makes its appearance) and plunge into the abysmal darkness of history’s most remote corners. They reenact—yet another mode of historicizing and storytelling much favored by artists growing up in a culture of accelerated oblivion—reconstruct, and recover. Happy to honor their calling, these artists seek out the facts and fictions of the past that have mostly been glossed over in the more official channels of historiography, such as the “History Channel” itself.3 They invariably side with both the downtrodden and the forgotten, reveal traces long feared gone, revive technologies long thought (or actually rendered) obsolete, bring the unjustly killed back to (some form of) life, and generally seek to restore justice to anyone or anything that has fallen prey to the blinding forward march of History with a capital, monolithic “H”—that most evil of variations on the Hegelian master narrative.

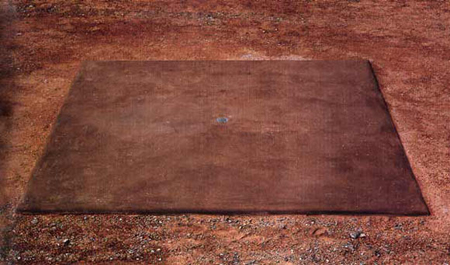

Jeff Wall, Fieldwork. Excavation of the floor of a dwelling in the former Sto:lo nation village, Greenwood Island, Hope, B.C., August, 2003, Anthony Graesch, Dept. of Anthropology, University of California at Los Angeles, working with Riley Lewis of the Sto:lo band, 2003. Transparency in lightbox, 219.5 x 283.5 cm.

Collection of the artist. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

The reasons for this oftentimes melancholy (and potentially reactionary) retreat into the retrospective mode of historiography are manifold, and are of course closely related to the current crisis of history both as an intellectual discipline and as an academic field of enquiry. After all, art’s obsession with the past, however recently lived, effectively closes it off from other, possibly more pressing obligations, namely that of imagining the future, of imagining the world otherwise (“differently”). Our culture’s quasi-pathological systemic infatuation with both the New and the Now (“youth”) has effectively made forgetting and forgetfulness into one of the central features of our contemporary condition, and the teaching of history in schools around the globalized world has suffered accordingly.

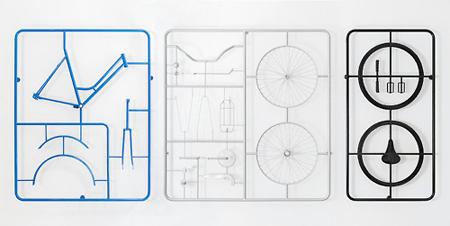

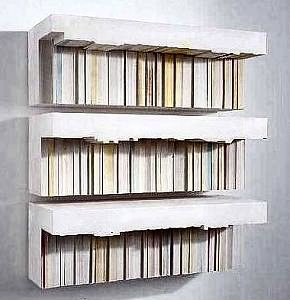

[This diagnosis of a “crisis of history” may strike the informed reader as unnecessarily alarmist and overblown: indeed, even the most cursory glance at the groaning bookshelves in the “History” section of one’s local culture mall—or its counterpart on Amazon.com—seems to suggest the opposite to be true. True, there is plenty of historiography out there, but it is of a very problematic, myopic kind that seems to add to the cultural pathology of forgetting rather than fight against it. It is a type of writing that prefers to hone in on objects (the smaller, the more mundane, and the less significant, the better) rather than people, the grand societal structures that harness them, or the events that befall them and/or help bring those structures into being. Virtually every little “thing” has become the subject of its own (strictly “cultural”) history of late, from the pencil to the zipper, the cod, the porcelain toilet bowl, the stiletto, the potato, or the bowler hat. It does not require too great an imaginative effort to discern the miserable political implications of this obsession with detail, novelty, and the quaint exoticism of the everyday (best summed up by the dubious dictum “small is beautiful”). Indeed, it seems sufficiently clear that the relative success story of this myopic micro-historiography, with its programmatic suspicion of all forms of grand historicization, is related both to today’s general state of post-ideological fatigue as well as to the political evacuation (or de-politicization) of academia, of which the “crisis of history” is precisely such an alarming, potent symptom.]

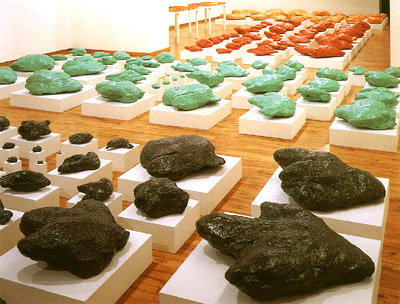

Roy Arden, Versace, 2006.

Archival pigment print, 25 x 21 inches.

In this sense, art has doubtlessly come to the rescue, if not of history itself, then surely of its telling: it is there to “remember” when all else urges us to “forget” and simply look forward—primarily to new products and consumerist fantasies—or, worse still, inward. Indeed, this new mode of discursive art production boasts an imposing critical pedigree, a long history of resistance and refusal: the eminent hallmarks, as we know, of true vanguardism.

One geopolitical region whose recent (and rewardingly traumatic) history has become especially prominent with art’s turn towards history-telling and historicizing (its turn away from both the present and the future), is post-communist Central and Eastern Europe—the preferred archeological digging site (if only metaphorically) of many well-read artists whose work has come of age in the broader context of the globalized art market of the last decade and a half. Ironically enough, the region’s triumph was wholly determined by the demise of the system of state socialism that so many of us now seek to memorialize.

[It is perhaps unnecessary to add here that the majority of these amateur archeologists hail from the “West,” where there may still exist certain pockets of nostalgia for the ideological clarity, among other things, of the Cold War era, when Central and Eastern Europe could be imagined as something radically “different,” belonging to “another” political world entirely—hence also its quasi-inexhaustible appeal to critical art: art that is committed to “making a difference.” Obviously, a similar type of nostalgia is also felt by a younger generation of artists from the former Eastern Bloc—but differently so, and the generational shift is of crucial importance here.4]

In their cultivation of the retrospective and/or historiographic mode, many contemporary art practices inevitably also seek to secure the blessing (in disguise) of History proper: in an art world that seems wholly dominated by the inflationary valuations of the market and its corollary, the fashion industry (“here today, gone tomorrow,” or, “that’s so 2008”), time, literally rendered as the subject of the art in question, easily proves to be a much more trustworthy arbiter of quality than mere taste or success. Hence the pervasive interest of so many younger artists and curators in the very notion of anachronism or obsolescence and related “technologies of time”: think of Super 8 mm and 16 mm film, think of the Kodak slide carousel, think of antiquated, museum-of-natural-history-style vitrines meant to convey a sense of the naturalization of history, or of time proper. Perhaps many artists use these tried-and-tested methods of history as a science, or as a mere material force (the archival mode ranks foremost among these methods), in hopes that some of its aristocratic sheen will rub off on their own products or projects, or otherwise inscribe them and their work in the great book of post-History . . .

Goshka Macuga, When Was Modernism, 2008.

Mixed media, installation at Museum voor Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen (MuHKA).

Courtesy the artist, Kate MacGarry and MuHKA

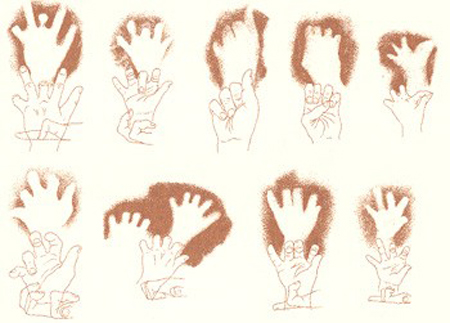

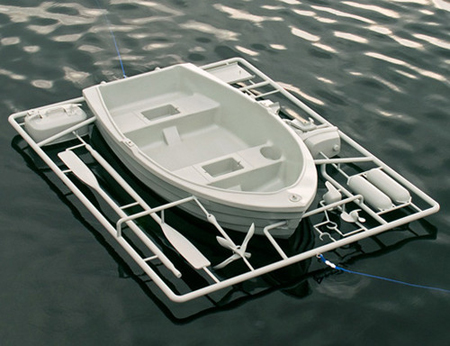

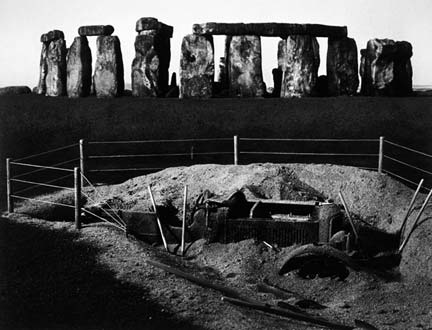

One of the ways in which this historiographic “turn” has manifested itself lately is though a literalized amateur archeology of the recent past: digging. Archeology’s way of the shovel has long been a powerful metaphor for the various endeavors that both spring from the human mind and seek to map the depths of, among other things, itself. Perhaps the most famous example of this would be psychoanalysis (or “depth psychology”), in which the object of its archaeological scrutiny is the human mind. Throughout a history that stretches far beyond the work of, say, Robert Smithson, Haim Steinbach, or Mark Dion, psychoanalysis has long been a source of fascination and inspiration for the arts. Certainly, one could conceive of an exhibition consisting solely of artistic images of excavation sites, of “art about archeology.” The truth claims of art often quote rather literally and liberally from the lingua franca of archeology: artists often refer to their work as a labor of meticulous “excavation,” unearthing buried treasures and revealing the ravages of time in the process; works of art are construed as shards, fragments (the Benjaminian ciphers of a revelatory truth), traces preserved in sediments of fossilized meaning. Depth delivers artistic truth: that which we dig up (the past) in some way or other must be more “real” and therefore also more “true” than all that has come to accumulate afterwards to form the present. This also says something about why we think the present is so hard to explain.

Likewise, the scrupulous archeological ethic of unending patience and monastic devotion to detail—seamlessly mirrored in its preferred optic, that of the clinical close-up—is, in spirit, close to the obsessive labor or “science” of art-making that often requires plodding through hours, days, and weeks of menial rubble-and-manure-shoveling before something that may (or may not) resemble a work of art emerges. Michelangelo’s sculptures of dying slaves wresting themselves free from the marble in which the artist “found” them captive continue to provide what is perhaps the archeological paradigm’s most gripping image.5 Furthermore, there can also be no archeology without display—the modern culture of museum display (if not of the museum itself) is as much “produced” by the archeologist’s desire to exhibit his or her findings as it is by the artist’s confused desire to communicate his or hers. After all, the logical conclusion of all excavatory activity is the encasing of History’s earthen testimony within a beautiful, exquisitely lit, amply labeled glass box—an apt description, indeed, of much artistic and meta-artistic or curatorial activity of the last decade and a half.6 Finally (and most importantly, perhaps), art and archeology also share a profound understanding—and one might say that they are on account of this almost “naturally” inclined to a Marxist epistemology—of the primacy of the material in all culture, the overwhelming importance of mere “matter” and “stuff” in any attempt to grasp and truly read the cluttered fabric of the world. The archaeologist’s commitment is to earth and dirt, hoping that it will one day yield the truth of historical time; the artist’s commitment is to the crude facts of his or her working material (no matter how “virtual” or, indeed, immaterial this may be), which is equally resistant to one-dimensional signification and making-sense, equally prone to entropy—yet likewise implicated in a logic of truth-production.

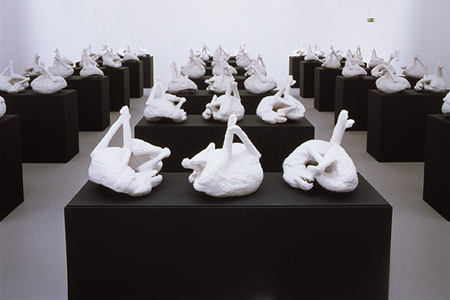

Mark Dion, The Birds of Antwerp, 1993.

Mixed media, installation at Museum voor Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen (MuHKA).

In this critical Bataillean sense of a “base materialism”—a materialism from which all traces of formalist idealization have been evacuated—both art and archeology are also work—hard and dirty work, certain to remind us of our bodily involvement in the world. The archeological imaginary in art produces not so much an optics as it does a haptics—it invites us, forces us to intently scratch the surface (of the earth, of time, of the world) rather than merely marvel at it in dandified detachment. By thus intensifying our bodily bondage to a world that, like our bodies themselves, is made up first and foremost of matter, the alignment of art and archeology compensates for the one tragic flaw that clearly cripples the purported critical claims and impact of the current “historiographic turn” in art: its inability to grasp or even look at the present, much less to excavate the future.

e-flux journal #4

1 Walter Benjamin, “Excavation and Memory,” in Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2, 1931–1934, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, trans. Rodney Livingstone et al. (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), 576. Benjamin continues: “Above all, he must not be afraid to return again and again to the same matter; to scatter it as one scatters earth, to turn it over as one turns over soil. For the “matter itself” is no more than the strata which yield their long-sought secrets only to the most meticulous investigation. That is to say, they yield those images that, severed from all earlier associations, reside as treasures in the sober rooms of our later insights.” In the words of Peter Osborne, “Benjamin’s prose breeds commentary like vaccine in a lab,” Radical Philosophy, no. 88 (1998), →.

2 Mark Godfrey’s much-discussed essay “The Artist as Historian,” published in October 120 (2007), has become a local landmark of sorts. In it Godfrey states that “historical research and representation appear central to contemporary art. There are an increasing number of artists whose practice starts with research in archives, and others who deploy what has been termed an archival form of research” (142–143). He then goes on to focus on the work of one artist-as-historian in particular, Matthew Buckingham, forgoing the opportunity to offer the reader an explanation, no matter how speculative or tentative, as to why historical research and representation in general have become so central to contemporary art (again). Furthermore, as the work of a historian does not necessarily coincide with that of a historiographer, the job description that I would suggest is more accurate with regard to contemporary art practice: the act of “writing” (or, more broadly, narrating) adds a key distinction here.

3 This analogy prompts the memory of a similar televisual metaphor: when asked about the socio-political import of hip-hop, Public Enemy’s charismatic frontman Chuck D famously called the genre “the CNN of Black America,” in that it also provides its (supposedly marginalized) constituency with informal, unofficial history lessons and alternative views of mainstream “news”—or any fact of world history that may have fallen by the wayside in a process of ideological homogenization. Likewise, it has sometimes been said that many of the last decade’s most important mega-exhibitions (biennials, documentas, Manifestas—not art fairs) at times came to resemble documentary film festivals where the likes of Discovery Channel, the History Channel and the National Geographic Channel come to exchange their wares, making the art world look like something akin to a BBC World program of politically disenchanted aesthetes and TV-hating intellectuals.

4 The historiographic turn in “post-socialist” European art specifically is the subject, among other things, of Charity Scribner’s aptly titled Requiem for Communism, published by MIT in 2003. An exhaustive list of practitioners from post-socialist “Eastern” Europe who self-reflexively mine this particular field would be hard to compile; however, such a list would definitely have to include the names of Chto Delat, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Marysa Lewandowska & Chris Cummings, Goshka Macuga, David Maljković, Deimantas Narkevicius, Paulina Olowska, and to a certain extent also Anri Sala and Nedko Solakov. Artists from the “West” who have consistently devoted their attention to the intricate meshwork of some of these histories include Gerard Byrne, Tacita Dean, Laura Horelli, Joachim Koester, Susanne Kriemann, Sophie Nys, Hito Steyerl, Luc Tuymans, and many more.

5 Michelangelo’s statement with regard to the slave figures, that he was “liberating them from imprisonment in the marble,” also recalls the famous motto that guided his near-contemporary Albrecht Dürer: “Truly art is firmly fixed in Nature. He who can extract her thence, he alone has her.” We could easily replace Dürer’s idealized, quasi-divine Nature in this last quote with Culture, History, or Time in order to paint a fairly accurate picture of the thinking that goes on behind (or, better still, underneath) much historiographic-art production today: this strand of contemporary art is as much a business of extraction as it is one of excavation.

6 A great many artists have been “mining the museum” in recent years, and their interest in museological displays and genealogical frameworks certainly belongs to the broader thrust of the historiographic turn in contemporary art: Fred Wilson coined the geological formula, Louise Lawler and Mark Dion did some exploratory groundwork (quite literally, in the latter’s case), while Carol Bove, Goshka Macuga, Josephine Meckseper, Jean-Luc Moulène and Christopher Williams rank among the micro-genre’s better-known contemporary practitioners. Many of the artists working in this field of a critical museology have a complicated relationship with the habitus of institutional critique, to which it is obviously indebted; they certainly “long for” the museum much more strongly and directly than the first generation of institutional critics would ever allow themselves to. In the speleological imaginary of “mining the museum”—note the sexual undertones of this metaphor—the museum has become an object of desire as much as an object of critique, a cavity as much as an excavation site.